Content Warning: Contains mentions of the Holocaust, chronic illness, ableism, mental health issues, chronic pain and suffering.

Disclaimer: This article is meant for educational purposes and is based on the author’s personal experiences and opinions. It is not to be substituted for medical advice. Please consult your own doctor or therapist before changing or adding any new treatment protocols. This post also contains affiliate links. It will cost you nothing to click on them. I will get a small referral fee from purchases you make, which helps with the maintenance of this blog (approx. $100/month). Thank you!

Table of Contents

What Does the Book, “Man’s Search for Meaning”, Have to Do with Chronic Illness???

With over 10 million copies sold, Viktor Frankl’s book, “Man’s Search for Meaning”, is one of the most popular books of our times. I am sure that there are many great reviews of this book out there already. But the angle that I’d like to take here is from the perspective of a person with chronic illness.

Many of the points that Viktor Frankl make are highly relatable to when you live with chronic illness, trapped in a body of pain. I would exclaim ever so often whilst reading the book, “Yes, this is exactly what it feels like to live with chronic illness, too!”

Even the psychological coping methods that the prisoners used are similar to how many of us manage our chronic pain. Having said that, I am in no way discounting the experiences of the men in the concentration camps. They suffered horrid, unimaginable crimes of war.

Culture has an influence on how we express or deal with emotions and pain. But emotions and pain are still things we can all relate to no matter who we are, or where we come from. A billionaire for example, is no less immune to heartache as anyone else on the streets. The grief from the loss of a loved one is just as heartbreaking for a person in a modern city, as it is for someone from a hill tribe.

Viktor Frankl wrote the book in only nine days, yet it is full of thought provoking questions and wisdom. “What is the meaning of life?” His thoughts on this timeless question are easy to understand and written with bosom knowledge. I only wish that I could have read it in the original German version with all nuances retained.

In this post I will share some of the insights I gleaned from Viktor Frankl’s book, “Man’s Search for Meaning”, and how they relate to chronic illness life.

Originally Published on: 04 April 2017

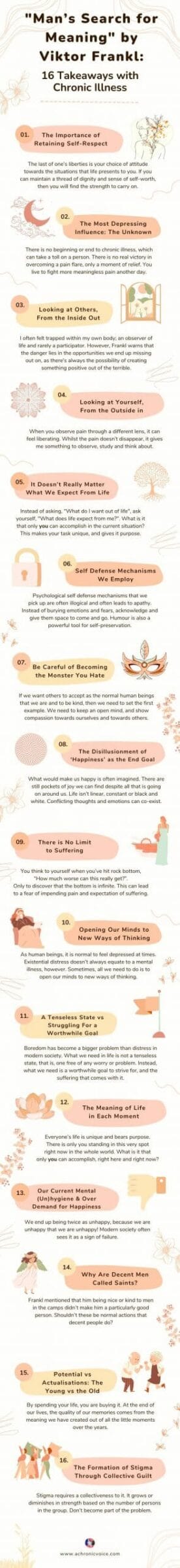

P.s. For a visual summary, view the infographic at the end of the post!

Pin to Your Life Lessons & Chronic Illness Boards:

1. The Importance of Retaining Self-Respect

➡️ How maintaining a shred of dignity can be like a life buoy on the stormy seas of chronic illness. ⬅️

Through Viktor Frankl’s observation, the men who possessed a rich inner life often outlasted those who were tough in physical capacity only. The last of one’s liberties is your choice of attitude towards the situations that life presents to you.

Living with chronic illness over the years has made me realise how important self-respect is. In fact, I believe that dignity, more so than love from others, is the virtue that keeps a person alive. When you’ve hit rock bottom, the number of people who love you, or how much they love you, no longer matters.

You think to yourself, “They’d be better off without me”. Or, “Why should they have to suffer for my problems?”.

These negative thoughts are likely shaded with depression or a defeated mindset. Some people don’t even have the ‘luxury’ of such thoughts, because they don’t have family or people they can rely on to begin with.

But if you can maintain a thread of dignity and sense of self-worth, then you will find the strength to carry on. To remain dignified is to remain responsible. Not only towards others, but also towards yourself. You begin to die when you lose faith in the future.

Many of the men who passed away in the camps did so of ‘health reasons’. Yet it was clear to those around them that these men had given up on hope right before their passing.

This leads me to wonder: Do many of those who die from chronic illness actually die from despair above all?

2. The Most Depressing Influence: The Unknown

➡️ There is no beginning or end to chronic illness. This sort of pain is meaningless, and can take a toll on a person. ⬅️

As Viktor Frankl observed, the most depressing influence in the camps was the unknown. The men didn’t know how long they’d have to endure their suffering.

As a person with chronic illness, we do have an answer to that – we will have to live with the pain until the day we die. But the pain levels and severity of side effects do fluctuate.

Chronic pain is highly unpredictable and symptoms change by the day, and even by the hour. This unpredictability can develop into anxiety and depression, as you’re always on the alert for sudden pain.

Acute pain can also feel unbearable, such as that experienced with a UTI or by giving birth. Yet there is often some comfort in the fact that the pain will pass. This in turn can grant you the strength to pull through.

Chronic pain on the other hand is of a chaotic nature. A sense of purpose may give a chronically ill person focus, but we mostly need to endure for the sake of enduring.

This takes a toll on a person. There is no real victory in overcoming a pain flare, only a moment of temporary relief. You live to fight more meaningless pain another day.

3. Looking at Others, From the Inside Out

➡️ How being chronically ill makes me feel more like an observer of life, and rarely a participator. ⬅️

The men who laboured within the camps were able to look at life on the outside through the fences, yet this meant nothing to them. It was akin to a dead man peering into a foreign world.

I have often felt that way myself, trapped within my own body. I feel like I’m just ‘looking outside’ of myself wherever I go. An observer of life, and rarely a participator.

The freedom that others have is exclusive to them. They can come and go as they please, fuelled by an unbelievable amount of energy. This vitality is magical to me, something I can only admire from afar but never grasp.

However, Frankl warns that the danger with this division lies in the opportunities we end up missing out on. There is always the possibility of creating something positive out of the terrible. But it is something we must actively look for.

4. Looking at Yourself, From the Outside in

➡️ How observing chronic pain through a different lens can feel liberating. ⬅️

Then there is the inversion; Looking at yourself from the outside in. Frankl would sometimes transport himself into the future using his imagination. And research has shown that imagination is a crucial element in self-identity and self-preservation.

He would picture himself giving lectures on the current torments he was experiencing. Thus, everything became experimental and scientific to him, interesting even.

Sometimes I also picture myself ‘outside’ of my body, where I separate pain from thought. Not in a transcendental way, but more from an analytical, third person point of view.

Even doctors often have no explanation as to what’s happening to me, or what to do about it. Our bodies are such fascinating things, including the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of pain.

The pain doesn’t disappear when I observe myself in the third person. It’s more like putting it under a microscope, which gives me something to observe, study and think about.

I then become the scientist running the investigation, and no longer feel like the subject or victim. Chronic pain becomes a little more bearable this way. Chronic pain then, has some sort of purpose. Perhaps even more so, because I am experiencing it first hand, ‘for real’.

5. It Doesn’t Really Matter What We Expect From Life

➡️ How to derive purpose from life by approaching it with humility, instead of entitlement. ⬅️

This was the best lesson I learned from the book, which helped me through some depressive moments as well. Frankl urged the men who were deep in despair to change their attitudes towards life.

To ask, “What does life expect from me?”, instead of, “What do I want out of life?”.

To come from a place of humility and look at ourselves as being the question of life, instead of questioning her with an air of constant arrogance and entitlement.

Living with chronic illness has also made me realise that the purpose of life is simply, ‘to be’. It is to hold constant communion with life and ask her, “What is it that you expect from me, in this very moment?”. And then to get up and go fulfil that duty to the best of my ability.

If life requires that I suffer in the present moment, then I will need to accept this job with grace. To ask myself, then, “What is it that only *I* can do in such a situation?”

This makes my task unique, and gives it purpose. Should you lose all hope in this life, then your one task is to continue hoping, despite.

I don’t find this emotionless or stoical at all. In fact, I find it to be a peaceful thought. To quote Mel Robbins, “You have been assigned this mountain, to show others that it can be moved.”

6. Self Defense Mechanisms We Employ

➡️ Psychological self defense mechanisms that we learn are often illogical, and why humour is one of the best coping strategies. ⬅️

Some of the men in the camps had built up apathy as a form of psychological self defense. If they braced themselves for the ultimate end, then what was the worst that could happen next?

Frankl shared an interesting anecdote: The men were walking through a beautiful field one day, yet none of them could feel happy about it. Such beauty was so foreign from their reality that they had depersonalised themselves from feeling any pleasure.

Dealing with chronic illnesses year after year can build up this same nonchalant attitude, too. It is a neutral state, devoid of too much pain, or too much joy. In fact, I started to dread stability and joy, because something worse would always happen after.

I even took it a step further and became self-destructive. Whenever life got a little ‘too stable’, I would do something to rock the boat. I tried to use minor sufferings as a talisman for major ones. I needed to seek out psychological help so that I would stop ruining my life, and trust that happiness can exist as is, without strings attached.

I hoped, dreamed and willed of escape, which in chronic illness terms, means a remission. Yet I knew that if and when that did happen, I would probably panic and be unable to accept it as reality.

As I sit here updating this post 7 years later, I am glad to say that my mental health is in slightly better shape. Depression, anxiety and panic attacks still happen. But I’ve learned that I can take away some of their power, simply through the acknowledgement of their existence. Instead of trying to run from or bury my fears and emotions, I make space for them. That is how they come, and eventually go.

The Power of Humour

He also notes that humour is another means to self preservation, and might even be the best form of it. Humour takes the edge off terrible situations, and casts it in an amusing light. There is victory in that sense, as you have managed to enjoy a little something even within the throes of agony.

There are only a few people who get my morbid sense of humour, but making light of dire situations and chronic pain helps me to cope. It gives me courage by diminishing the severity of the problem, thus taking away some of its power.

7. Be Careful of Becoming the Monster You Hate

➡️ If we want society to believe in the invisibility of our pain and to show empathy, then we need to set the first example. ⬅️

How does a person start to look like what they hate? By focussing the entirety of their thoughts on the subject, until they begin to think in its likeness.

As Nietzsche said, “He who fights with monsters should be careful lest thereby become a monster. And if thou gaze long into an abyss, the abyss will also gaze into thee.”

In “Man’s Search for Meaning”, Viktor Frankl claims that this can happen when freedom is suddenly regained. Many of the men became the oppressors towards their former oppressors upon their release.

One needs to hold firm to their values and have a deep sense of self-knowledge. Otherwise, the risk of degenerating into arbitrariness is very real.

How Chronic Pain Can Dismantle a Person

Chronic pain and stigma from society can also build up with similar toxicity in those with chronic illness. If we wallow in misery and pain for too long, a bitterness starts to set in.

If we aren’t careful, it starts to harden into a crust. We want those who have ignored our plight to feel our pain. “Now they know what it feels like. That’ll show them!”

We dismiss others who are in pain, because their pain can’t be as bad as ours. This rottenness can even be found within chronic illness communities. There are truly some supportive people and networks out there. But there are also those that are breeding grounds for negativity and unkindness.

The Irony of Being in Pain All the Time

It’s a bit of an irony, and even takes some effort to not morph into a hypocrite. You will find no lack of finger pointing, blame, shame and disbelief within a community that needs to stand together more so than others.

We bottle up our frustration with society’s ignorance and lack of empathy. Then we regurgitate the hate, anger and judgement back onto our own communities. It’s not hard to find heated arguments, as we accuse each other of exaggeration, ‘misinformation’ or stupidity.

We become arrogant in the knowledge of our illnesses, and reject any new suggestions. (P.s. My biggest pet peeve is unsolicited advice, and there’s also heaps of harmful, illegitimate advice out there. But there are also one or two gems that we may just be missing out on, if we’re too disgruntled to even consider them!)

If we want others to accept as the normal human beings that we are and to be kind, then we need to set the first example. We need to keep an open mind, and show compassion towards ourselves and towards others.

We need to forgive the unforgivable, or it will forever take up space within our heart, mind and soul. Space that is precious, sacred and could be put to better use.

8. The Disillusionment of ‘Happiness’ as the End Goal

➡️ Happiness is often imagined. There are pockets of joy we can find in everyday life. ⬅️

When you are in the throes of suffering and strive for ‘happiness’ as the end goal, you can forget that unhappiness still exists when and if you do get there.

This may happen to some of us who go into remission from chronic illness. Life doesn’t consist of happy moments only. Pain, grief and loss still exist no matter how healthy we are. This can lead to disappointment again.

Life isn’t linear, constant or black and white. It is a melange of both bright and dull colours, a spectrum of opinions and perspectives, twists, turns and more. Conflicting thoughts and emotions can co-exist.

We need to remember that in order to keep things in perspective. This helps us to be able to appreciate a moment as is, empathise with others, and also to understand ourselves better.

What would make us happy is often imagined. There are still pockets of joy we can find despite all that is going on around us. Joy is also a more stable element than happiness. Whilst happiness is often emotional and temporary, joy is transcendent of that.

9. There is No Limit to Suffering

➡️ Repeat: There is no limit to suffering. ⬅️

When the men in the camps thought that they had reached the limits of human suffering, they learned that pain really has no ceiling. It’s always possible to suffer some more.

This is a concept that people with chronic illness can grasp. Almost every year I’d learn of a new diagnosis I had, or would need to undergo yet another surgery. This leads to a fear of impending pain and expectation of suffering. I felt like a soldier that was constantly on the move and going into battle.

You think to yourself when you’ve hit rock bottom, “How much worse can this really get?”. Only to discover that the bottom is infinite. This leads me to my next point…

10. Opening Our Minds to New Ways of Thinking

➡️ Chronic illness teaches our brain to be on the constant lookout for pain. We need to unlearn that and stop it from becoming a bad habit. ⬅️

As human beings, it is normal to feel depressed at times. We all experience it. Existential distress doesn’t always equate to a mental illness, however. Sometimes, all we need to do is to open our minds to new ways of thinking.

Those who live with chronic pain tend to be hyper-aware of their bodies. Chronic pain trains you to monitor the slightest change within it.

Any new pain or ache arouses suspicious and we start to analyse it. Previous undesirable experiences have taught us that it’s always better to be a little paranoid, and nip a problem in the bud.

‘Wait and see what happens’ has often escalated to regrettable levels of pain and distress. A pain flare that could have been avoided, if only we had done something about it a little sooner.

Whilst this habit has helped me with pain management more often than not, I also started to find things that weren’t even there to begin with. Many times I’d go to the A&E out of prudence, only to be sent home with an ‘all-clear’.

It took me a long time to unlearn this fear and to retrain my brain to consider the possibility of a decent outcome. I had to resist the urge to hit the panic button too quickly, because that was also exhausting to deal with.

A question I use to help me cope and make decisions is this: “What would benefit my over all well-being most in the present moment?”. Then I’d try and work outwards from there, step by little step.

This does take some practice and also experience. The more you live with chronic illness, the more you familiarise yourself with it, quirks and all.

It isn’t always a perfect self-assessment, but self-knowledge is always useful. Sometimes other ailments are mistaken for our ‘regular’ chronic pain, hence the importance of flexibility and being open to change.

11. A Tenseless State vs Struggling For a Worthwhile Goal

➡️ Life isn’t about reducing pain but increasing meaning, and the additional struggles that the chronically ill face when pain is all they know. ⬅️

The existential vacuum is a first world, modern day problem. Boredom has become a bigger problem than distress.

Viktor Frankl mentions that what we need in life is not a tenseless state, that is, one free of any worry or problem. Instead, what we need is a worthwhile goal to strive for, and the suffering that comes with it.

I like his illustration using the architecture of arches in buildings. To strengthen an arch, you do not lessen the pressure placed upon it. Instead, you must increase the pressure so as to make it more compact. It isn’t about decreasing tension in our lives, but increasing the tension for meaning.

The Added Struggle with Chronic Illness

Many of us consumed by chronic pain might actually view a tenseless state as preferable. I’d give anything to escape from intense chronic pain. It terrifies me. I’d rather live in a meaningless vacuum than to suffer day and night.

This is something that the average healthy person might not understand, with statements like ‘what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger’ as mantras for the era.

In that sense, those of us who are stuck with chronic illness may have a bigger challenge to deal with. Everything can feel meaningless when pain is all-consuming. Goals become redundant, even frivolous. All you want is for the pain to stop.

We need to convince ourselves that whatever we’re aiming for is worth the hellfire that comes with it. Those who have no family or support network in place will find this even harder. But all we can do is to try from a place of hope and humanity.

12. The Meaning of Life in Each Moment

This is one of Viktor Frankl’s most well-known quotes: “For the meaning of life differs from man to man, from day to day and from hour to hour. What matters, therefore, is not the meaning of life in general but rather the specific meaning of a person’s life at a given moment.”

Everyone’s life is unique and bears purpose. There is only you standing in this very spot right now in the whole world. Mind blowing, if you think about it that way.

Logotherapy, which is Frankl’s form of therapy and amongst the three important pillars in psychology, sees in essence human existence as ‘responsibility’. What is it that only you can do, right here and right now, for the better?

He uses movies as a metaphor: Every scene that you watch has meaning from moment to moment, yet you only know what the whole point to it is at the end. Life’s like that too. We all need to play our part, and play it well until the very end.

So for those who are suffering in one way or another – hang in there. Who knows what will happen next? And even if the ‘movie’ doesn’t have a happy ending, it usually has a captivating plot or profound insight to it.

It is a role that life insists upon and has selected you for, because there is no better protagonist for it. In the words of Dave Grohl, “No one is you and that is your power.”

13. Our Current Mental (Un)hygiene & Over Demand for Happiness

➡️ When a state of activity is valued more than a state of passivity, does it make us less humane? ⬅️

One interesting point he makes is the modern idea that people ought to be happy, and that unhappiness is a symptom of maladjustment. We end up being twice as unhappy, because we are unhappy that we are unhappy! Society often sees it as a sign of failure.

Thich Nhat Hanh also said, “Our idea of happiness is our biggest obstacle to happiness”, which rings true here as well.

We are also a realistic generation, because we know the extent of humankind’s potential for empathy and also cruelty.

The symbol of this era is achievement. It adores the young, the successful and worships happiness. It ignores everything else because it sees no value in them. Our sense of being and dignity are often replaced by our sense of usefulness, with the latter seen as more valuable and admirable.

Those of us with chronic illness often feel like we’re living out our twilight years, even though we may only be 20. Many of us can’t work full-time or even part-time, and struggle with pain from the moment we wake, until we go to bed again.

Are Those with Chronic Illness the Dregs of Society?

Based on outward appearances, we’re underachievers and seen as the dregs of society. What do we have to give, offer or show off about? Are we burdens on the system?

We are the epitome of everything modern society does not adore. Nothing about our situation is pleasant or conjures envy. Often it conjures sympathy, only because people realise that they’re human just like us, and that this could happen to them someday, too.

Your self-worth and self-identity are called into question with every new diagnosis. Before I became chronically ill, I was an overachiever. This was only because I had the energy to push myself beyond my limits.

Now I need to pace myself; To force myself to stop even before I come anywhere near my limits, or risk a pain flare. It’s a bit like a moth to a flame though, and many of us still take that risk on a rare good day.

14. Why Are Decent Men Called Saints?

Frankl mentioned that him being nice or kind to men in the camps didn’t make him a particularly good person. Shouldn’t these be normal actions that decent people do?

Survival has always been at stake throughout the centuries. In the modern jungle, decent acts are lauded as ‘amazing’, whilst rudeness and unkindness are ‘normal’. “Welcome to the real world”, we quip.

Easy access to a wealth of information has made us jaded, opinionated and sometimes misinformed. What has happened to us as human beings?

15. Potential vs Actualisations: The Young vs the Old

➡️ Experiences and the meanings we assign to them become the building blocks of our memories, and of our psychological quality. ⬅️

Frankl brings up an interesting point – that the old are more enviable that the young. What blasphemy as mentioned above! To be feeble, infirm, and slow? There must be a way to prolong youth…

He states the young are full of potential and possibilities, but these have yet to crystallise into realities. Old folks have concrete actualisations. They own actual assets within their memories, and are rich with experiences.

By spending your life, you are buying it. Health, finances, and responsibilities can limit physical quality. But we can choose part of our psychological quality. At the end of our lives, the quality of our memories comes from the meaning we have created out of all the little moments over the years.

The Value of Our Chronic Illness Experiences & Why We Should Share Them

Chronic illness expands our experiences in life and often our perspective on it as well. Like how becoming a parent ‘unlocks a new door’ and provides more insight into life, so does chronic illness.

Whilst these experiences may not be desirable, there is still value to them. Don’t let them rust under a closed lid. Display them, if not for appreciation, then for knowledge. If not for art and humanity, then for science and truth.

16. The Formation of Stigma Through Collective Guilt

➡️ Stigma needs to be fed to grow in strength. Don’t become part of the problem. ⬅️

As humans, we tend to place everyone in the same classification, based on the action of one person. We refer to a single trait or object from a vile person, then associate it with vileness. It’s lazy logic, or really, illogical.

For example: “Jack the murderer always has an apple in his hand. Therefore, association with apples is evil.” (You can swap this with a hijab if you want.)

Making such assumptions and associations are not only superstitious, but also stigmatising. Stigma requires a collectiveness to it. It grows or diminishes in strength based on the number of persons in the group. And stigma can be destructive if it gets out of hand.

If only one person believes that mental illness is a ‘conspiracy’, there isn’t much to fear. But if a million people believe that to be true, the fear intensifies and spills over into society.

The Stigmatisation of Mental Illness in Everyday Life

Movies are a good example once again. The mentally ill are often portrayed as cold-blooded murderers. In reality, many of these patients do more harm to themselves than to others.

Another example where this stigmatisation happens quite a bit is when a criminal is diagnosed with mental illness in the news. Many of these keyboard warriors don’t even read the article. They don’t bother to find out more about the diagnosis or about mental illness.

They just get on their high horse and crucify said criminal without mercy. Maybe even gain a sense of satisfaction from their self-righteousness.

“A pathetic excuse.” “A stupid reason.” “We should rip her eyeballs out, pour burning coals on them and torture her to death.”

How humane of them.

Laws exist for a reason, and mental illnesses are not an excuse to escape them. But these same people pass gross misjudgement on the mentally ill in everyday life as well.

“Depression is a pathetic excuse for not cleaning the house. She’s such a bad mother.” “Anxiety is a stupid reason to miss work for. He’s so lazy and irresponsible.” “We need to give her a good slap to get her out of her head and face up to real life.”

Have these people ever considered that they’re part of the problem? The stigma and ignorance surrounding a mental health issue may deter a person from seeking the help they need. So get out of the way and don’t be part of the problem.

Concluding Thoughts & Further Applications

This is a book that I will definitely need to read again several times. I am sure that there’s much more to learn, especially over the different phases of my life.

I plan to use my life experiences to open cans of worms that the average person cannot, because they don’t know how, or have no right to. I can initiate discussions and delve deeper into sensitive topics that people daren’t ask, yet are curious about. They might be thinking, “Am I being insensitive? Is this okay to ask? Will people see me as a fool or monster?”.

Anyone can join in the discussion of a subject, but those with experience add insight from actualisations. Having suffered something is to earn the right to speak about it without fear. And this power to speak up is a big deal.

Pin to Your Chronic Illness & Life Lesson Boards:

Click to Download the Infographic in a Larger Version Here.

If you liked this article, sign up for our mailing list here so you don’t miss out on our latest posts. You will also receive an e-book full of uplifting messages, quotes and illustrations, as a token of appreciation!

-

For More Insight:

- Viktor Frankl: Why believe in others

- Viktor Frankl: Logotherapy and Man’s Search for Meaning

-

References:

- Nangyeon Lim (2016). Cultural differences in emotion: differences in emotional arousal level between the East and the West, Integrative Medicine Research. Volume 5, Issue 2, Pages 105-109, ISSN 2213-4220, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imr.2016.03.004.

- He, C. H., Yu, F., Jiang, Z. C., Wang, J. Y., & Luo, F. (2014). Fearful thinking predicts hypervigilance towards pain-related stimuli in patients with chronic pain. PsyCh journal, 3(3), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1002/pchj.57

- Dezutter, J., Casalin, S., Wachholtz, A., Luyckx, K., Hekking, J., & Vandewiele, W. (2013). Meaning in life: an important factor for the psychological well-being of chronically ill patients?. Rehabilitation psychology, 58(4), 334–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034393

- Costanza A, Chytas V, Piguet V, Luthy C, Mazzola V, Bondolfi G, Cedraschi C. (2021). Meaning in Life Among Patients With Chronic Pain and Suicidal Ideation: Mixed Methods Study. https://formative.jmir.org/2021/6/e29365. JMIR Form Res. 5(6):e29365 DOI: 10.2196/29365

- Paul T.P. Wong. Editor(s): Michel Hersen, William Sledge (2002). Logotherapy. Encyclopedia of Psychotherapy, Academic Press. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B0123430100001343. Pages 107-113. ISBN 9780123430106. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-12-343010-0/00134-3.

- Ziebland, S., & Wyke, S. (2012). Health and illness in a connected world: how might sharing experiences on the internet affect people’s health?. The Milbank quarterly, 90(2), 219–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00662.x

- Mascayano F, Toso-Salman J, Ho YCS, et al. Including culture in programs to reduce stigma toward people with mental disorders in low- and middle-income countries. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2020;57(1):140-160. doi:10.1177/1363461519890964

I thought I had commented on this when you posted it! I read Man’s Search For Meaning the summer of 2019 and it is certainly one of my top reads to refer to friends who are ill or going through trauma. I like how you laid out each point and explained it so well! This one really stuck out for me:

“How being chronically ill makes me feel more like an observer of life, and rarely a participator.”

It explains how I’m feeling this year so well. Definitely working through despair this year and cannot wait for 2022 to be over, but then I think back and realize I felt that way about 2020 and 2021 too. Gotta try and get out of that mindset, I guess.

Thanks for reading and sharing your thoughts Carrie, I appreciate it! Yes let’s hope 2023 is kinder to the Tiger zodiacs out there like us lol. 2022 is definitely tops on my list of ‘worst years ever’.

I hope you’re coping okay. We can dip our toes in and participate in life every once in a while still. We just need to be observant and aware when the opportunities do pop up (so says Frankl!) 😀 Sending lots of hugs.

I love everything about this: “For the meaning of life differs from man to man, from day to day and from hour to hour. What matters, therefore, is not the meaning of life in general but rather the specific meaning of a person’s life at a given moment.”

Too often we are busy looking around us at all the ways the things we need to do, improvements that need to be made, and ways we can succeed and give meaning to our lives at some point. But, if we are always focusing on the future we’re missing out on some of the greatest moments that exist here and now. Adopting a more mindful approach to life has made a HUGE change in my life over the last couple of years.

Hi Britt, I’m so happy for you that your life’s been for the better, and also congrats on your new business! That sounds so exciting! And thank you so much… it’s one of my favourite books and food for thought 🙂

What a wonderful post! This book has been on my “must read” list for a long time, but I have seen quotes from it in many places and often thought that it perfectly fit the situations of chronic illness. You’ve done a beautiful job here of distilling some of those lessons.

Now I really MUST read it for myself!

Sue

Live with ME/CFS

Hi Sue, thank you for your comment! Yes it really is very reflective and reminiscent about a lot of things. It’s a sensitive topic though so I sometimes get yelled at for comparing chronic illness, but I think human suffering is universal, in a sense. Sending you good thoughts and hope you’re doing well!

Sheryl,

Thank you for this. It sounds like an amazing book, and I love how you applied those lessons to the disabled identity. I especially loved the section on having purpose. Pressure on the arch increases its strength. I have always tried to give myself goals and a sense of purpose for precisely these reasons. I want, need, to do more than exist. Sometimes that something is getting a deeper understanding of FND, more often it’s working on my blog or some other project, but it seems like I feel best when I am working on something beyond myself, something outside of me. That’s when I feel most whole, when I feel best.

Most welcome, Alison. Some (healthy) people didn’t find the book that interesting, but I guess I was just astounded by the parallels with chronic illness. I was also reprimanded on Twitter for this post by a disabled Jew who said that I wasn’t permitted to compare it with chronic illness, something along the lines that they suffered more. But I think Mr. Frankl would have been okay with it (but who knows), as these life lessons are universal, and it’s good to take something away from it imho. Sending love to you!

There is so much to learn from this book and this post Sheryl. But I think I will need to re-read this post a few times over to really absorb the learnings from it.

I especially liked…

04. Looking at Yourself, from the Outside In

12. The Meaning of Life in Each Moment

…it’s all got me thinking as I rest away today.

Thank you for sharing this book with us Sheryl.

Hi Shruti, thank you for your thoughtful comments as always 🙂 Yes it’s an entire book I need to re-read myself! I hope you have a good rest. My body hasn’t been too well of late either, so we’ll both need to rest as much as we can. Sending gentle hugs!

I’ll be honest and say that I haven’t heard of this book before, but it sounds so interesting. I resonate with what you say about pain having no ceiling. I think perhaps only those with chronic illness will fully grasp this. A migraine attack can easily get worse, as so many other conditions. We can easily hit the panic button as you say, and it’s tough to try and get back to remembering that life can be so positive too.

Hi Claire, it’s okay, there are so many books out there, it’s nigh impossible to know every single one of them, famous or otherwise! And yes, I think it’s a concept that only those with chronic illness can fully grasp. You just get beaten up – and beaten up worse – time and time again. After I got through my first horrible encounter with unbearable pain, I thought that it would come to an end and that was the worst it could be. But boy was I wrong – there isn’t a ceiling. Sending love and yes, life can be full of beauty, too. In fact, life IS beauty and tragedy all at once 🙂

Great post. I love all your graphics and how used Dr Frankl’s applications in them ✨ and written in the prize for those of us living a chronic condition life. It’s not an easy life to live so we all hope we can help others based on our “Beenthere, done that & learned this” so that others will months have to.

Thank you for the great read ✨

Hi Lisa,

Thank you so much for taking the time to read. I am very happy that you enjoyed it! Yes, while I was reading this book there were just too many moments where I could relate to the suffering and I knew I just had to write a post about it. Wishing you the best your health can be!

Enjoyed reading this article especially looking at these applications from the perspective of someone with a chronic illness. You’re so right that it can be very much like living like a prisoner by living in our sick bodies – and yes absolutely that should give us the right to speak out about our experiences of this. Hopefully by doing so we can help others understand a little more as well as it being helpful for us to not bottle up how we feel! I think I will have to read this book!

Hi Emma,

Thank you for taking the time to read! I am very happy that it was useful to you 🙂 Yes I’d definitely recommend this book, it was very easy to read, and very thought provoking! x